Wie schnell sich die Wahrnehmung eines ganzen Landes ändern kann! Woran dachten Sie bis vor kurzem bei Island? Vulkane & Geysire, unberührte wilde Natur, Islandpferde, Wikinger, Walfang... Als auf der Feier am Wochenende bekannt wurde, daß ich einiges mit Island zu tun habe, kam als erste Frage stets: “Und, hatten Sie auch ein Konto in Island?”

Wie schnell sich die Wahrnehmung eines ganzen Landes ändern kann! Woran dachten Sie bis vor kurzem bei Island? Vulkane & Geysire, unberührte wilde Natur, Islandpferde, Wikinger, Walfang... Als auf der Feier am Wochenende bekannt wurde, daß ich einiges mit Island zu tun habe, kam als erste Frage stets: “Und, hatten Sie auch ein Konto in Island?”

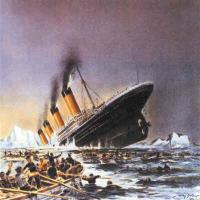

Island heute? “The victim of an economic 9/11", hieß es zuletzt in der Financial Times. “The Icelandic krona’s freeze in the capital markets had now spilled over into the day-to-day transactions of Icelanders abroad. Holidaymakers and business travellers venturing “til Útlanda”, as it is called, found their credit cards refused, and those wishing to buy foreign currency could not find willing sellers, aside from one or two who limited their purchases to €200.

Iceland is the only country in the world that indexes its loans in addition to charging interest. This means that when Icelanders borrow IKr1,000 from the bank and inflation increases by 5 per cent, the bank increases their debt to IKr1,050 at the end of the year. A great deal for the bank and fine for you, too – so long as the property’s value and your salary are increasing by inflation and more. The majority of Icelandic mortgages are based on this punitive system and with inflation running at nearly 20 per cent, they will see their IKr1,000 loan turn into a IKr1,200 loan. The interest burden will increase proportionally. This is bad enough, but when coupled with falling house prices, it means that many face a particularly savage variety of negative equity. The impact on highly geared borrowers, which in practice means most Icelanders, would be hard enough even with two incomes, but with unemployment set to soar, many households are going to go under.

Picture a pig trying to balance on a mouse’s back and you’ll get some idea of the scale of the problem. In a mere seven years since bank deregulation and privatisation, Iceland’s financial institutions had managed to rack up $75bn of foreign debt. Iceland’s banks borrowed more than $250,000 for every man, woman and child in Iceland, and placed an impossible burden on the modest reserves of the central bank in the event of default. And default they have.”

Der finanzielle Schaden ist gewaltig. Für die Volkswirtschaft, aber auch für fast jeden einzelnen Haushalt in Island. Doch darüber hinaus hat er auch Schäden in der isländischen Seele hinterlassen. Isländer, erläutert der einige Jahre in Island lebende Autor des Artikels, “survived plague, famine, earthquakes and volcanoes. There were times when some even considered abandoning the island. But they stayed on. They stayed and survived. Icelanders will tell you that only the fittest survived, but that is only half the story, because survival requires another key attribute: stubbornness. And Icelanders have it in spades. It is a national trait, and they view it not as a weakness but as a virtue. It comes from experiencing hardship and enduring it. It means finding satisfaction in a simple task done well and sticking to it; finding comfort and solace in family and kinship and being bound by those familial bonds and duties. And perhaps most important of all, it means believing in the independence of the individual as part of the fabric of nationhood, and fighting for that independence. Put simply, the country has values.

And this is what sets this catastrophe apart from the earthquakes and plagues of former years. This is a man-made disaster and worse still, one made by a small group of Icelanders who set off to conquer the financial world, only to return defeated and humiliated. The country is on the verge of bankruptcy and, even more important for those of Viking stock, its international reputation is in tatters. It hurts.

Many became uncomfortable with the excesses of the Viking Raiders. The liveried private jets, the Elton John parties, the residences in St Moritz, New York and London and the yachts in St Tropez – all flaunted in Sed og Heyrt, Iceland’s equivalent of Hello! magazine – were not, and this is important, they were not Icelandic. There was a strong undertow of public opinion that felt that all this ostentatious celebration of lavish lifestyles and excess was causing the nation to disconnect from its thousand-year heritage.

One of the most telling images was the departure of Jon Ásgeir’s private jet on news that the government had nationalised Glitnir Bank (in which his investment vehicle Stodir was a leading shareholder), wiping out his shareholding and rattling the debt-burdened house of cards that is his Baugur business empire. Painted black and as sleek as a Stealth bomber, the aircraft was photographed taxiing from its hangar by Morgunbladid, a daily newspaper. Like the last helicopter out of Saigon, the departure of Ásgeir’s jet symbolised the end of an era, the last act of Iceland’s debt-fuelled spending spree.” (FT, 14.11.08)

... link (1 Kommentar) ... comment